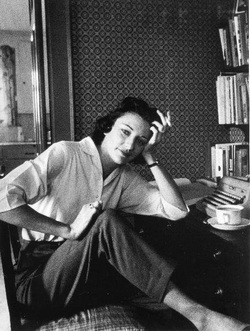

Liane Strauss

|

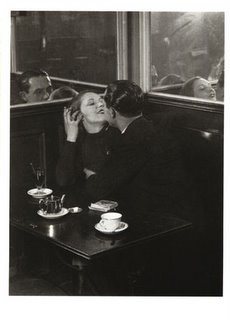

One of the pleasures of building this section of the website is to have been plunged into the poetic world of the late Michael Donaghy, whose alumni are disproportionately represented on my guest list. If he gave them water to drink during seminars, there must have been something in it. Among the leaders of a pack that seems to consist almost entirely of leaders, Liane Strauss has got something going in her poetry that it took Donaghy himself adequately to describe. If I may paraphrase him here, he said that her poems were held together by their impetus, which was made possible by her acute sense of rhythm. This particle-beam velocity, it seems to me, is exactly the right thing to emphasise about her work. Not that any of it could have been composed hastily: but the effect of its crafty putting-together is to create an onrushing rhetoric that comes perilously close, on occasions, to being its own subject. Whether for reader or writer, there is always a danger in getting carried away; but she circumvents it by the precision with which she sees the world, and especially the interior world of romance. She can drive a standard romantic line straight at the wall of cliche and spin the wheel at the last moment ("The nothings you whispered were not sweet") so that the whole idea turns into a memorable night out, with a picnic on the canal bank at dawn as the car finishes sinking out of sight. But she has no chance of turning off the glamour that her hurtling forms generate, like girls painted on the engine cowlings of WW II American fighter planes taking off from East Anglian airfields made to look doubly wan by the shining silver imported machinery. It is all very American and no doubt deplorable but I can't imagine that anyone will cry "Yankee go home" in any voice above a whisper. Her work is helping to provide the dazzling evidence that there is a new school of poets in London for whom the Atlantic has simply disappeared.

|

Where we Started

If people can dream together, we dream together.

This is the way it always starts.

Out of the darkness of the streets that lie between us

and the river rising like a rampart raised to part the city

from its dreamed and dreaming counterpart across the river

falling like leaves shed by the streetlamps every evening

dreaming they shed light and keep the city from the river,

we make our way back to each other’s side.

It doesn’t take long. It never does,

not in the dream we dream together.

I know you and you know me so well,

all we need to find each other is to sleep.

Inside this world more real than real

we’re always more and more awake.

It’s how we dream it.

And maybe because it’s a collaboration,

like a double negative,

what we end up with is the opposite of a dream,

where I’m about to tell you something

but you already know it,

and you’re about to tell me,

since we’re dreaming together,

so that we stop and start and smile and stop again

like two strangers in a doorway.

But whatever it is that parts,

like dawn the lips of the curtains,

like the last look,

tears us from each other’s side,

you, half way across the labyrinth of dream

and boulevard, and me, in my half,

at the end of the street

at the end of the night,

the streetlamps stepping back in their own darkness

where we started.

This is the way it always starts.

Out of the darkness of the streets that lie between us

and the river rising like a rampart raised to part the city

from its dreamed and dreaming counterpart across the river

falling like leaves shed by the streetlamps every evening

dreaming they shed light and keep the city from the river,

we make our way back to each other’s side.

It doesn’t take long. It never does,

not in the dream we dream together.

I know you and you know me so well,

all we need to find each other is to sleep.

Inside this world more real than real

we’re always more and more awake.

It’s how we dream it.

And maybe because it’s a collaboration,

like a double negative,

what we end up with is the opposite of a dream,

where I’m about to tell you something

but you already know it,

and you’re about to tell me,

since we’re dreaming together,

so that we stop and start and smile and stop again

like two strangers in a doorway.

But whatever it is that parts,

like dawn the lips of the curtains,

like the last look,

tears us from each other’s side,

you, half way across the labyrinth of dream

and boulevard, and me, in my half,

at the end of the street

at the end of the night,

the streetlamps stepping back in their own darkness

where we started.

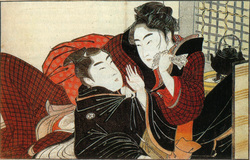

Variations on a Theme by Lady Suwō

Pillowed on your arm

only for the dream of a spring night,

I have become the subject of gossip,

although nothing happened.

Pillowed on your dream,

I come and go all spring,

taking pleasure in gossip

as though nothing happened.

Pillowed on my arm,

I confide only in myself

the dream of your arm,

my endless dream of your arm.

Pillowed on my dream,

I no longer drift out into a spring night

but make plans before sunset,

as if something happened.

Pilloried by love

I sip the dram of gods

from the spring of night –

Where’s the harm in that?

Pillowed on the dream of your arm,

a mute owl on a bare bough

in a starless barn

shrouded in snow.

Disarmed by a spring night,

powerless against dreams,

assailed by gossip,

I throw the windows open.

Pillowed on the spring night

of your arm –

I can’t sleep.

Pillowed on the gossip of your arm

I have become an object of ridicule

in my own eyes.

only for the dream of a spring night,

I have become the subject of gossip,

although nothing happened.

Pillowed on your dream,

I come and go all spring,

taking pleasure in gossip

as though nothing happened.

Pillowed on my arm,

I confide only in myself

the dream of your arm,

my endless dream of your arm.

Pillowed on my dream,

I no longer drift out into a spring night

but make plans before sunset,

as if something happened.

Pilloried by love

I sip the dram of gods

from the spring of night –

Where’s the harm in that?

Pillowed on the dream of your arm,

a mute owl on a bare bough

in a starless barn

shrouded in snow.

Disarmed by a spring night,

powerless against dreams,

assailed by gossip,

I throw the windows open.

Pillowed on the spring night

of your arm –

I can’t sleep.

Pillowed on the gossip of your arm

I have become an object of ridicule

in my own eyes.

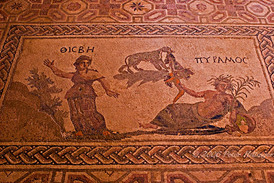

The Little Death

When I played Thisbe in eleventh grade,

Miss Wilhelmina Penrest, up to then

my favourite English teacher, chose

John O'Leary, my own secret Pyramus,

to play the part of Pyramus. I loved

to study him each afternoon in Study Hall

framed like a print of the daydreaming Keats

in a small gap among the stacks which I had

delicately engineered. He was my first

pair of blue eyes — two pale blue shallow pools

the lightest shade of late July chlorine.

He had this pasty Irish skin, this fog

of wiry hair, this empty-headed grin.

Maybe she knew. Though she asked Henry Mersey

to play Wall, almost as keen to have me kiss

the chink his fingers made as I was loath

to do it. And what possessed her to press

Sally Wayne, who shone through acne craters

every time that Henry Mersey like the sun

came in the room, to take the part of Moon?

All this I could forgive. Although she very nearly

lost my love for good when to play The Lioness

Miss Penrest picked that fizgig Helen Rosemount-Hill.

Rehearsals were a daily agony.

With every sally Henry Mersey made

I'd shrink and Sally Wayne would wax with hope.

And every time I sought John out, there was

that Helen Rosemount-Hill beneath her heap

of auburn hair, all set to pounce. Between

that and the way that Henry Mersey had

of mercilessly being in the way,

as if he understood things like a god

and not a wall, or else had spent a lifetime

in the office of a wall, immured

to human suffering, and so a god,

a very genius of a wall,

I couldn't get anywhere near John O'Leary.

I did believe things couldn't get any worse

than having to endure The Lioness

offer to read my part (my part!) with Pyramus.

Poor John, he never was that swift, still tripping

on his lines and cues and props, but did

he have to take her up with such alacrity?

It burned the way I wished that bloody sword

had it been steel and not collapsible on touch

would burn when every day I plunged it in my breast.

It didn't help that, all along, as I could tell

from how Miss Penrest flipped the pages

of her book and tapped her fingers with her pen

and fiddled with her glasses on their chain,

I was still falling short of Thisbe.

But I was wrong.

I still don't know why I went back.

I didn't need my script, I knew my role,

I was already late, it was getting dark,

I hated the smell of that auditorium.

I almost didn't hear the mobbled knocking

from the stage and turn to see the art department's

masterpiece, Old Ninny's tomb, shuddering

like the haunches of a fly-beleaguered cow,

the half unpainted mulberry banging at it

doggedly, the papier-maché trunk beating

its appliqués of bark like an indignant goose.

Next day when Henry Roughcast Wall accosted me

and offered me my book, I talked with him.

When Helen Lioness taught Sally Moon in France

it's called the little death, she paled and fled

in search of Thisbe to whom she confessed

that she had never even gotten to first base.

And when I, Thisbe, held both Pyramus

and John O'Leary limp and clammy in my arms,

and dead, and gazed down on that glist'ning brow,

where I counted eleven pimples and made out

in the corners of his mouth egg evidence,

I thought I could see what I was in for --

the foolish comedy of walls and moons,

the long succession of little deaths --

and I let Thisbe have her head, shaking

her fists, tearing her hair, beating her breast

in a spectacular display of deathless love

until there was no more of that wretched fidgeting.

Miss Wilhelmina Penrest, up to then

my favourite English teacher, chose

John O'Leary, my own secret Pyramus,

to play the part of Pyramus. I loved

to study him each afternoon in Study Hall

framed like a print of the daydreaming Keats

in a small gap among the stacks which I had

delicately engineered. He was my first

pair of blue eyes — two pale blue shallow pools

the lightest shade of late July chlorine.

He had this pasty Irish skin, this fog

of wiry hair, this empty-headed grin.

Maybe she knew. Though she asked Henry Mersey

to play Wall, almost as keen to have me kiss

the chink his fingers made as I was loath

to do it. And what possessed her to press

Sally Wayne, who shone through acne craters

every time that Henry Mersey like the sun

came in the room, to take the part of Moon?

All this I could forgive. Although she very nearly

lost my love for good when to play The Lioness

Miss Penrest picked that fizgig Helen Rosemount-Hill.

Rehearsals were a daily agony.

With every sally Henry Mersey made

I'd shrink and Sally Wayne would wax with hope.

And every time I sought John out, there was

that Helen Rosemount-Hill beneath her heap

of auburn hair, all set to pounce. Between

that and the way that Henry Mersey had

of mercilessly being in the way,

as if he understood things like a god

and not a wall, or else had spent a lifetime

in the office of a wall, immured

to human suffering, and so a god,

a very genius of a wall,

I couldn't get anywhere near John O'Leary.

I did believe things couldn't get any worse

than having to endure The Lioness

offer to read my part (my part!) with Pyramus.

Poor John, he never was that swift, still tripping

on his lines and cues and props, but did

he have to take her up with such alacrity?

It burned the way I wished that bloody sword

had it been steel and not collapsible on touch

would burn when every day I plunged it in my breast.

It didn't help that, all along, as I could tell

from how Miss Penrest flipped the pages

of her book and tapped her fingers with her pen

and fiddled with her glasses on their chain,

I was still falling short of Thisbe.

But I was wrong.

I still don't know why I went back.

I didn't need my script, I knew my role,

I was already late, it was getting dark,

I hated the smell of that auditorium.

I almost didn't hear the mobbled knocking

from the stage and turn to see the art department's

masterpiece, Old Ninny's tomb, shuddering

like the haunches of a fly-beleaguered cow,

the half unpainted mulberry banging at it

doggedly, the papier-maché trunk beating

its appliqués of bark like an indignant goose.

Next day when Henry Roughcast Wall accosted me

and offered me my book, I talked with him.

When Helen Lioness taught Sally Moon in France

it's called the little death, she paled and fled

in search of Thisbe to whom she confessed

that she had never even gotten to first base.

And when I, Thisbe, held both Pyramus

and John O'Leary limp and clammy in my arms,

and dead, and gazed down on that glist'ning brow,

where I counted eleven pimples and made out

in the corners of his mouth egg evidence,

I thought I could see what I was in for --

the foolish comedy of walls and moons,

the long succession of little deaths --

and I let Thisbe have her head, shaking

her fists, tearing her hair, beating her breast

in a spectacular display of deathless love

until there was no more of that wretched fidgeting.

Ceci n'est pas

The love letters you sent me were not love letters.

The nothings you whispered were not sweet.

The promises you promised were not promises.

Your kisses betrayed nothing.

The things you never wanted me to see

were not the things you didn’t want me not to see.

You weren’t the one I thought you were to be.

I was exactly what you expected.

The smoke that bellowed from the cinema

was not the fire that broke the paper moon.

The nest that piped its passion to the sea

was not the lookout gone to dream among the briars.

The lies you told me were not lies.

The truth that you professed was not the truth.

Love is not love and nothing is more real

than who we’re not and what we never had.

The nothings you whispered were not sweet.

The promises you promised were not promises.

Your kisses betrayed nothing.

The things you never wanted me to see

were not the things you didn’t want me not to see.

You weren’t the one I thought you were to be.

I was exactly what you expected.

The smoke that bellowed from the cinema

was not the fire that broke the paper moon.

The nest that piped its passion to the sea

was not the lookout gone to dream among the briars.

The lies you told me were not lies.

The truth that you professed was not the truth.

Love is not love and nothing is more real

than who we’re not and what we never had.

Leaving Eden

The motor’s running and I’m leaving Eden.

It’s gotten too small, too cramped. It’s too green.

I’ve packed my bags, taken my best face cream,

shaken the apple tree until my wormy heart fell at my feet.

It’s not the serpent. I didn’t need convincing.

It’s not in my nature to be happy to ignore what I know.

Can’t remember when I first went suspicious.

If I’m disenchanted with the past at least I’m something,

something to the core.

There never was a paradise on earth, or heaven.

Each fleshy fist of fruit harbours its seed.

Nothing has changed, nothing was ever how it seemed

in Eden, and if it was, I can’t imagine it was me.

The motor’s running, the asphalt is seething.

My bare legs stick to vinyl slick with sweat.

The air of motion now will run its fingers through me

and like Atlantis underwater I’ll forget.

It’s gotten too small, too cramped. It’s too green.

I’ve packed my bags, taken my best face cream,

shaken the apple tree until my wormy heart fell at my feet.

It’s not the serpent. I didn’t need convincing.

It’s not in my nature to be happy to ignore what I know.

Can’t remember when I first went suspicious.

If I’m disenchanted with the past at least I’m something,

something to the core.

There never was a paradise on earth, or heaven.

Each fleshy fist of fruit harbours its seed.

Nothing has changed, nothing was ever how it seemed

in Eden, and if it was, I can’t imagine it was me.

The motor’s running, the asphalt is seething.

My bare legs stick to vinyl slick with sweat.

The air of motion now will run its fingers through me

and like Atlantis underwater I’ll forget.

The morning is the hardest. It is morning

The morning is the hardest. It is morning

when I nearly don’t remember. But I remember

once how you said morning should come later,

which never made much sense, until this morning.

The middle of the day, my heart, reminds me

of a road I’ve never been on, it is endless.

The evening is the hardest, it’s the darkness.

I shut my eyes and count until it finds me.

One by one the hours fly off, they leave without me.

I can’t keep them and I can’t see where they take you.

The night won’t end and when you don’t forsake me

and stroke my cheek and say, “You can’t come with me,”

it makes no sense, but then the sky is turning

and dark descending dawn dawns and it’s morning.

when I nearly don’t remember. But I remember

once how you said morning should come later,

which never made much sense, until this morning.

The middle of the day, my heart, reminds me

of a road I’ve never been on, it is endless.

The evening is the hardest, it’s the darkness.

I shut my eyes and count until it finds me.

One by one the hours fly off, they leave without me.

I can’t keep them and I can’t see where they take you.

The night won’t end and when you don’t forsake me

and stroke my cheek and say, “You can’t come with me,”

it makes no sense, but then the sky is turning

and dark descending dawn dawns and it’s morning.

Proof

You stay away.

You sit beside me.

You have nothing to say.

You stay away.

You stay away.

You come round

Only to refute my supposition that

You stay away.

I’m profligate with my affection

But not with you.

I have nothing to say.

You make me wait.

You stay away.

Love is not susceptible to proof.

You sit beside me.

You have nothing to say.

You stay away.

You stay away.

You come round

Only to refute my supposition that

You stay away.

I’m profligate with my affection

But not with you.

I have nothing to say.

You make me wait.

You stay away.

Love is not susceptible to proof.

Muse

I’m the dame, and you’re the dick.

My eyes are greener than the new kid –

Why does he look so damn familiar? –

my legs are longer than the San Andreas Fault,

and it’s a call. But it’s my heart

that’s flawed and hard and colder still

than all the loveless bodies hard-knock cops

fish from the star-crossed, moon-lorn Bay

and blacker than La Brea’s blackest pit.

That’s how you see me.

And I can see that you’re about to pour

that bleak long inextricable worn look

stiffer than the drink you just passed up

into the endless pitch of my impenetrable Ray Bans.

You’re screening Stairs of Sand again.

The old print ticks with fraying static threads,

the murky script rises and surfaces

out of the soundtrack thick as blackstrap with cliché

like fresh rot from the dark

where I’m the con and you’re the mark.

I’m the kiss and you’re the tell.

You’re the how, I’m the why.

I’m the blinding booze, the sucker bet,

and you’re the loner with the heart of gold,

that fatal yen for just the kind of trouble

you know better than to stick

your supersensitive neck out for

and in spite of which,

because there’s no such thing as love,

because no one ever does anything for nothing,

because you can’t even begin to figure out what the hell you’re doing here,

and I never asked you,

you won’t stop until you save me.

My eyes are greener than the new kid –

Why does he look so damn familiar? –

my legs are longer than the San Andreas Fault,

and it’s a call. But it’s my heart

that’s flawed and hard and colder still

than all the loveless bodies hard-knock cops

fish from the star-crossed, moon-lorn Bay

and blacker than La Brea’s blackest pit.

That’s how you see me.

And I can see that you’re about to pour

that bleak long inextricable worn look

stiffer than the drink you just passed up

into the endless pitch of my impenetrable Ray Bans.

You’re screening Stairs of Sand again.

The old print ticks with fraying static threads,

the murky script rises and surfaces

out of the soundtrack thick as blackstrap with cliché

like fresh rot from the dark

where I’m the con and you’re the mark.

I’m the kiss and you’re the tell.

You’re the how, I’m the why.

I’m the blinding booze, the sucker bet,

and you’re the loner with the heart of gold,

that fatal yen for just the kind of trouble

you know better than to stick

your supersensitive neck out for

and in spite of which,

because there’s no such thing as love,

because no one ever does anything for nothing,

because you can’t even begin to figure out what the hell you’re doing here,

and I never asked you,

you won’t stop until you save me.

Frankie, Alfredo

after Catullus

I’ll give you some of your sour grapes to suck on,

since you suspect my poems only sell because

I tart them up like high school girls in Camden.

A real poet must live in stripy jumpers

and two pair of glasses, eschew irony

and mascara and tend countrified passions

lest helpless young men divagate or query

their maudlin eds. and over-the-hill tutors,

whose backs are stiff and abacuses rusty

(hence their tendency to curse their barstools, beat

hendecasyllables with lifeless digits),

why they have to pickle their rhetorical

figures in the formaldehyde of bitters.

And you, full of voluptuous objection,

because my verses spill over with push-up

bras and low-riding tangas think I’m a girl!

Name the dawn. I’ll take your mouths and your money,

both hands tied behind my back, in a blindfold

and ten bona fide inches of stiletto,

one after the other. Or both concurrent.

And no seconds. We’ll just see who’s left standing.

since you suspect my poems only sell because

I tart them up like high school girls in Camden.

A real poet must live in stripy jumpers

and two pair of glasses, eschew irony

and mascara and tend countrified passions

lest helpless young men divagate or query

their maudlin eds. and over-the-hill tutors,

whose backs are stiff and abacuses rusty

(hence their tendency to curse their barstools, beat

hendecasyllables with lifeless digits),

why they have to pickle their rhetorical

figures in the formaldehyde of bitters.

And you, full of voluptuous objection,

because my verses spill over with push-up

bras and low-riding tangas think I’m a girl!

Name the dawn. I’ll take your mouths and your money,

both hands tied behind my back, in a blindfold

and ten bona fide inches of stiletto,

one after the other. Or both concurrent.

And no seconds. We’ll just see who’s left standing.

It’s Never Too Early for a Clean Slate

I’m blinking in the blank white light off the blinding sheets.

The voice beside my head has seen more of the world already

and it’s not even 7. She reassures me like a baby,

but I’m 42 if I’m a day, and I need to hear the forecast,

which I still haven’t learned has nothing to do with the weather.

The next 12 hours are playing like a film on the bathroom mirror.

I’m the atheist at the baptism, looking forward to lamb chops:

I merely survey the experience; my heart’s not in it.

When I release my grip the living end reverses into the tube.

And here is my first tall cup. It scalds

my gums, the parapets and vaults of my mouth,

and you’re talking to me in the native tongue

which was my own once, set like type,

or handprints in cement, as near second nature as Mother Nature,

but today I can’t make heads nor tails of anything you’re saying,

although I remain convinced if only I would try a little harder,

apply myself with more stick-to-itiveness,

I’ll be able to save you, or be myself saved,

from what, from the look in your eyes, is

some not-so-new or even unforeseeable disaster.

But then I realize I can’t even hear myself think,

that I’d need earplugs and a pneumatic drill

just to get through the words. And even your eyes

don’t hear me when, out of time, ideas and desperation,

I semaphore in my own dead language, remembering my father

telling me never to fall in love with a foreigner

or in the middle of the night he’d curse me.

But it’s only first thing in the morning,

and not the first time, by my troth,

I’ve failed to seize (let alone shuck) a pearl of wisdom

cast like an aspersion before me and time to go,

so I wave goodbye, which I see is an ambiguous

as well as an ambidextrous gesture. But at the same time

I also can’t see. And what choice do I have?

I don’t have two right hands, and we’re at the crossroads

of the breakfast table – the coast being clear, the toast being cold –

and I unbolt the chain, let slip the wards of God,

(or Whoever it is Whose gates these are) and,

tossing precaution and my only set of keys into the hedge,

I notice that it really isn’t too early yet,

and I’m brimming with hope, which has its disadvantages.

The voice beside my head has seen more of the world already

and it’s not even 7. She reassures me like a baby,

but I’m 42 if I’m a day, and I need to hear the forecast,

which I still haven’t learned has nothing to do with the weather.

The next 12 hours are playing like a film on the bathroom mirror.

I’m the atheist at the baptism, looking forward to lamb chops:

I merely survey the experience; my heart’s not in it.

When I release my grip the living end reverses into the tube.

And here is my first tall cup. It scalds

my gums, the parapets and vaults of my mouth,

and you’re talking to me in the native tongue

which was my own once, set like type,

or handprints in cement, as near second nature as Mother Nature,

but today I can’t make heads nor tails of anything you’re saying,

although I remain convinced if only I would try a little harder,

apply myself with more stick-to-itiveness,

I’ll be able to save you, or be myself saved,

from what, from the look in your eyes, is

some not-so-new or even unforeseeable disaster.

But then I realize I can’t even hear myself think,

that I’d need earplugs and a pneumatic drill

just to get through the words. And even your eyes

don’t hear me when, out of time, ideas and desperation,

I semaphore in my own dead language, remembering my father

telling me never to fall in love with a foreigner

or in the middle of the night he’d curse me.

But it’s only first thing in the morning,

and not the first time, by my troth,

I’ve failed to seize (let alone shuck) a pearl of wisdom

cast like an aspersion before me and time to go,

so I wave goodbye, which I see is an ambiguous

as well as an ambidextrous gesture. But at the same time

I also can’t see. And what choice do I have?

I don’t have two right hands, and we’re at the crossroads

of the breakfast table – the coast being clear, the toast being cold –

and I unbolt the chain, let slip the wards of God,

(or Whoever it is Whose gates these are) and,

tossing precaution and my only set of keys into the hedge,

I notice that it really isn’t too early yet,

and I’m brimming with hope, which has its disadvantages.