Programme Note

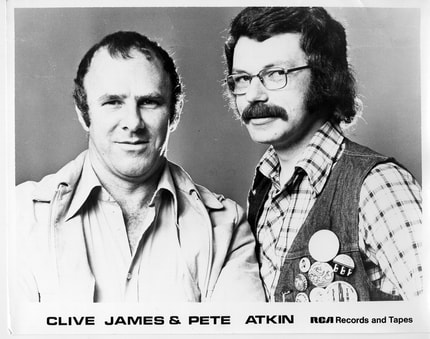

The show Pete Atkin and I perform on tour spares every expense. All we need is two chairs, a small table and a piano. If the theatre has no piano, Pete has a portable one in the back of the car. At the start of the show, the curtains are already open. We just walk on. The houselights remain undimmed. There are no theatrical effects. For two hours with an interval, he sings our songs and I do most of the talking in between. Nothing else happens, yet the show is far and away the most fruitful artistic venture I have ever been mixed up in. It wouldn't do for me to go on about how interesting I find it. The audience must judge. But I can say something about how much fun it is to do.

People who see the punishing tour schedule often commiserate with me. I wish they wouldn't, just as I wish young men wouldn't offer me their seat on crowded trains. I actually like being on the road. I was born to be a rock star. I just had to wait a few decades before it all happened: the endless travelling, the anonymous hotel rooms, the soulless existence. I can't get enough of all that stuff. I can't get enough of what it hasn't got. For one thing, it hasn't got complication. On tour, we know exactly what we're doing tomorrow. We're moving on to the next date, and we'll be eating Crunchy Bars in the car while listening to Creedence Clearwater Revival's greatest hits. Or anyway, we'll be eating Crunchy Bars while touring Britain. Touring Australia, we might be eating Cherry Ripe chocolate bars. Almost forty years ago, when Pete and I first met in Cambridge, I told him that the greatest taste thrill in every young Australian's life was the Cherry Ripe, eaten chilled from the fridge on a hot day. Over the last two years, as we toured Britain, I have told him many times that although Crunchy Bars are no doubt very nutritious, when we got to Australia he would at last find out what a Cherry Ripe can offer.

I think they're called Crunchy Bars. Pete buys them in bulk, and for all I know they're really called Neutrogrit or Yorkiechaff. I have never been able to look at the labels, which carry lists of all the desirable ingredients -sugar, calories, flavour, etc. - that the contents haven't got. This was the second year Pete and I took a song show on a 30-date tour of Britain. This year's show was entirely different from last year's but the living conditions were the same. Most of the daytime between performances we spent on the motorway, with him driving the car while I changed the CDs and the floor filled up with Crunchy Bar wrappers. (Neutrochaff. That was it.) In Australia, on those occasions when the dates are close enough together to drive between instead of fly, we will both be in the back of a tastefully luxurious chauffer-driven Lexus provided by the sponsor. Cherry Ripe wrappers will be folded up neatly and retained in the pocket. In Britain, most of the nights after performances were spent in one room each of a motorway travelodge. My room always looked so much like the room of the previous night that I would search it for a missing sock I left a hundred miles away. In Australia we have been promised proper hotel accommodation by our generous impresario, Jon Nicholls, but I have already told him, on Pete's behalf, that we quite like the simple lifestyle of the troubadour and won't mind at all if the taps in the bathrooms of our interconnecting suites are merely gold-plated instead of solid platinum.

After all, I'm not Saddam Hussein, nor is Pete Ivana Trump, although there have been lonely nights when I wished he were. In the first few days of last year's tour of Britain I quickly realised why this superficially austere way of life felt so sumptuous. It was because I had been thirsting for simplicity. After too many years in television I was worn out from being looked after. Television isn't the movies, but for anyone with his name in the title of the show the pampering is decadent enough. You never buy an airline ticket yourself. Someone puts the ticket in your hand. You soon get used to the huge basket of fruit waiting for you in the dressing room. You never eat any of it, but if the huge basket of fruit isn't huge enough then your agent will instruct you to leave it out in the corridor, thus to express anger at being slighted. In America it's a huge basket of huge fruit, and the artist's attorney weighs the apples.

Out on tour with our song show, I buy my own apples, and sometimes, even in Britain, I actually eat one, if we have run out of apple-flavoured Fergiecrunch. In Australia I will introduce Pete to the concept of limitless fruit, along with all the fast yet fabulously healthy food that can be bought by the roadside in a nation where not even the shopping malls have yet succeeded in becoming impersonal. It beats being waited on. (For one thing, you can't be waited on without being made to wait: have you noticed?) It's a simpler, saner way of life. I like to think it is matched by what we do on stage. Last year, getting ready for the first tour of our revival phase, we had to choose from more than a hundred songs we wrote in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the period in which Pete released six albums commercially and the record companies could never decide how to promote the stuff, because they didn't know what it was.

Thirty years later, with the blessed Internet having made the music industry less omnipotent at last, we were able to jump to the right conclusion: trust the audience. It doesn't matter what category our songs fall into, as long as people listen. The trick is to make sure nothing gets between the songs and the listeners. So the answer was, in both senses of the phrase, simplicity itself. The word got out, the tour organizers got their money back, and there was an unexpected result. For both of us, being on the road was like being back in our first days in the Cambridge Footlights, when we sat up late in the ratty old clubroom and wrote song after song because there was nothing to stop us except the usual essay crisis. Last year, as if all that elapsed time had never been, we started writing songs again.

This new show, the one we are taking all the way to Australia, is largely composed of the new work we have done in the past year, and I am sure that while we are on tour with this show there will be yet more new work getting started, and so on until I am old and grey. But I can just hear Pete saying: "You already are." He's a bit like that. A realist. It would be bad manners for me to praise his other qualities, except to say that if my lyrics helped him to discover the melodies of Winter Spring, then I have justified my long career of misspent youth. Whether or not my homeland thinks the same I will now find out. I am bringing home my best stuff. Much of it is the sort of thing I am lucky enough to be known for: tall tales about childhood in Australia, unreliable accounts of strange journeys to the magic land of Pracatan. But right at the heart of it is the work I am least known for, but would still like to be, if only as the writing partner of a unique musician. It is the work I have done with Pete Atkin, so I am very glad he has agreed to come with me, to see for the first time the amazing nation that he has heard me talk about so often.

People who see the punishing tour schedule often commiserate with me. I wish they wouldn't, just as I wish young men wouldn't offer me their seat on crowded trains. I actually like being on the road. I was born to be a rock star. I just had to wait a few decades before it all happened: the endless travelling, the anonymous hotel rooms, the soulless existence. I can't get enough of all that stuff. I can't get enough of what it hasn't got. For one thing, it hasn't got complication. On tour, we know exactly what we're doing tomorrow. We're moving on to the next date, and we'll be eating Crunchy Bars in the car while listening to Creedence Clearwater Revival's greatest hits. Or anyway, we'll be eating Crunchy Bars while touring Britain. Touring Australia, we might be eating Cherry Ripe chocolate bars. Almost forty years ago, when Pete and I first met in Cambridge, I told him that the greatest taste thrill in every young Australian's life was the Cherry Ripe, eaten chilled from the fridge on a hot day. Over the last two years, as we toured Britain, I have told him many times that although Crunchy Bars are no doubt very nutritious, when we got to Australia he would at last find out what a Cherry Ripe can offer.

I think they're called Crunchy Bars. Pete buys them in bulk, and for all I know they're really called Neutrogrit or Yorkiechaff. I have never been able to look at the labels, which carry lists of all the desirable ingredients -sugar, calories, flavour, etc. - that the contents haven't got. This was the second year Pete and I took a song show on a 30-date tour of Britain. This year's show was entirely different from last year's but the living conditions were the same. Most of the daytime between performances we spent on the motorway, with him driving the car while I changed the CDs and the floor filled up with Crunchy Bar wrappers. (Neutrochaff. That was it.) In Australia, on those occasions when the dates are close enough together to drive between instead of fly, we will both be in the back of a tastefully luxurious chauffer-driven Lexus provided by the sponsor. Cherry Ripe wrappers will be folded up neatly and retained in the pocket. In Britain, most of the nights after performances were spent in one room each of a motorway travelodge. My room always looked so much like the room of the previous night that I would search it for a missing sock I left a hundred miles away. In Australia we have been promised proper hotel accommodation by our generous impresario, Jon Nicholls, but I have already told him, on Pete's behalf, that we quite like the simple lifestyle of the troubadour and won't mind at all if the taps in the bathrooms of our interconnecting suites are merely gold-plated instead of solid platinum.

After all, I'm not Saddam Hussein, nor is Pete Ivana Trump, although there have been lonely nights when I wished he were. In the first few days of last year's tour of Britain I quickly realised why this superficially austere way of life felt so sumptuous. It was because I had been thirsting for simplicity. After too many years in television I was worn out from being looked after. Television isn't the movies, but for anyone with his name in the title of the show the pampering is decadent enough. You never buy an airline ticket yourself. Someone puts the ticket in your hand. You soon get used to the huge basket of fruit waiting for you in the dressing room. You never eat any of it, but if the huge basket of fruit isn't huge enough then your agent will instruct you to leave it out in the corridor, thus to express anger at being slighted. In America it's a huge basket of huge fruit, and the artist's attorney weighs the apples.

Out on tour with our song show, I buy my own apples, and sometimes, even in Britain, I actually eat one, if we have run out of apple-flavoured Fergiecrunch. In Australia I will introduce Pete to the concept of limitless fruit, along with all the fast yet fabulously healthy food that can be bought by the roadside in a nation where not even the shopping malls have yet succeeded in becoming impersonal. It beats being waited on. (For one thing, you can't be waited on without being made to wait: have you noticed?) It's a simpler, saner way of life. I like to think it is matched by what we do on stage. Last year, getting ready for the first tour of our revival phase, we had to choose from more than a hundred songs we wrote in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the period in which Pete released six albums commercially and the record companies could never decide how to promote the stuff, because they didn't know what it was.

Thirty years later, with the blessed Internet having made the music industry less omnipotent at last, we were able to jump to the right conclusion: trust the audience. It doesn't matter what category our songs fall into, as long as people listen. The trick is to make sure nothing gets between the songs and the listeners. So the answer was, in both senses of the phrase, simplicity itself. The word got out, the tour organizers got their money back, and there was an unexpected result. For both of us, being on the road was like being back in our first days in the Cambridge Footlights, when we sat up late in the ratty old clubroom and wrote song after song because there was nothing to stop us except the usual essay crisis. Last year, as if all that elapsed time had never been, we started writing songs again.

This new show, the one we are taking all the way to Australia, is largely composed of the new work we have done in the past year, and I am sure that while we are on tour with this show there will be yet more new work getting started, and so on until I am old and grey. But I can just hear Pete saying: "You already are." He's a bit like that. A realist. It would be bad manners for me to praise his other qualities, except to say that if my lyrics helped him to discover the melodies of Winter Spring, then I have justified my long career of misspent youth. Whether or not my homeland thinks the same I will now find out. I am bringing home my best stuff. Much of it is the sort of thing I am lucky enough to be known for: tall tales about childhood in Australia, unreliable accounts of strange journeys to the magic land of Pracatan. But right at the heart of it is the work I am least known for, but would still like to be, if only as the writing partner of a unique musician. It is the work I have done with Pete Atkin, so I am very glad he has agreed to come with me, to see for the first time the amazing nation that he has heard me talk about so often.